From the beginning of recorded history, people have practiced disinfection and sterilization, even though the existence of microorganisms was long unsuspected. The Egyptians used fire to sterilize infectious material and disinfectants to embalm bodies, and the Greeks burned sulfur to fumigate buildings. Mosaic law commanded the Hebrews to burn any clothing suspected of being contaminated with the leprosy bacterium.

Today the ability to destroy microorganisms is no less important: it makes possible the aseptic techniques used in microbiological research, the preservation of food, and the prevention of disease. The techniques described in this chapter are also essential to personal safety in both the laboratory and hospital (Box 7.1).

Definition of Frequently Used Terms

Terminology

is especially important when the control of microorganisms is discussed because

words like disinfectant and antiseptic often are used loosely. The situation is

even more confusing because a particular treatment can either inhibit growth or

kill depending on the conditions.

The

ability to control microbial populations on inanimate objects, like eating

utensils and surgical instruments, is of considerable practical importance.

Sometimes it is necessary to eliminate all microorganisms from an object,

whereas only partial destruction of the microbial population may be required in

other situations.

Sterilization [Latin sterilis, unable to produce offspring or barren] is the process by which all living cells, viable spores, viruses, and viroids are either destroyed or removed from an object or habitat. A sterile object is totally free of viable microorganisms, spores, and other infectious agents. When sterilization is achieved by a chemical agent, the chemical is called a sterilant.

In contrast, disinfection is the killing, inhibition, or removal of microorganisms that may cause disease. The primary goal is to destroy potential pathogens, but disinfection also substantially reduces the total microbial population. Disinfectants are agents, usually chemical, used to carry out disinfection and are normally used only on inanimate objects. A disinfectant does not necessarily sterilize an object because viable spores and a few microorganisms may remain.

Sanitization

is closely related to disinfection. In sanitization, the microbial

population is reduced to levels that are considered safe by public health

standards. The inanimate object is usually cleaned as well as partially

disinfected. For example, sanitizers are used to clean eating utensils in

restaurants.

It is

frequently necessary to control microorganisms on living tissue with chemical

agents. Antisepsis [Greek anti, against, and sepsis, putrefaction]

is the prevention of infection or sepsis and is accomplished with antiseptics.

These are chemical agents applied to tissue to prevent infection by killing

or inhibiting pathogen growth; they also reduce the total microbial population.

Because

they must not destroy too much host tissue, antiseptics are generally not as

toxic as disinfectants.

A

suffix can be employed to denote the type of antimicrobial agent. Substances

that kill organisms often have the suffix –cide [Latin cida, to kill]: a

germicide kills pathogens (and many nonpathogens) but not necessarily

endospores. A disinfectant or antiseptic can be particularly effective against

a specific group, in which case it may be called a bactericide, fungicide,

algicide, or viricide. Other chemicals do not kill, but they do

prevent growth.

If

these agents are removed, growth will resume. Their names end in -static [Greek

statikos, causing to stand or stopping]—for example, bacteriostatic and

fungistatic.

lthough

these agents have been described in terms of their effects on pathogens, it

should be noted that they also kill or inhibit the growth of nonpathogens as

well. Their ability to reduce the total microbial population, not just to

affect pathogen levels, is quite important in many situations.

The Pattern

of Microbial Death

A

microbial population is not killed instantly when exposed to a lethal agent.

Population death, like population growth, is generally exponential or logarithmic—that

is, the population will be reduced by the same fraction at constant intervals (table

7.1).

If

the logarithm of the population number remaining is plotted against the time of

exposure of the microorganism to the agent, a straight line plot will result

(compare figure 7.1 with figure 6.2). When the population has been greatly

reduced, the rate of killing may slow due to the survival of a more resistant strain

of the microorganism.

To

study the effectiveness of a lethal agent, one must be able to decide when

microorganisms are dead, a task by no means as easy as with macro-organisms. It

is hardly possible to take a bacterium’s pulse. A bacterium is defined as dead

if it does not grow and reproduce when inoculated into culture medium that

would normally support its growth. In like manner an inactive virus cannot infect

a suitable host.

Conditions

Influencing the Effectiveness of Antimicrobial Agent Activity

Destruction

of microorganisms and inhibition of microbial growth are not simple matters

because the efficiency of an antimicrobial agent (an agent that kills

microorganisms or inhibits their growth) is affected by at least six factors.

1. Population size. Because an equal fraction of a microbial population is killed during each interval, a larger population requires a longer time to die than a smaller one. This can be seen in the theoretical heat-killing experiment shown in table 7.1 and figure 7.1. The same principle applies to chemical antimicrobial agents.

2. Population composition. The effectiveness of an agent varies greatly with the nature of the organisms being treated because microorganisms differ markedly in susceptibility. Bacterial endospores are much more resistant to most antimicrobial agents than are vegetative forms, and younger cells are usually more readily destroyed than mature organisms. Some species are able to withstand adverse conditions better than others.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis, is much more resistant to antimicrobial agents than most other bacteria.

3. Concentration or intensity of an antimicrobial agent.

Often, but not always, the more concentrated a chemical agent or intense a physical agent, the more rapidly microorganisms are destroyed. However, agent effectiveness usually is not directly related to concentration or intensity. Over a short range a small increase in concentration leads to an exponential rise in effectiveness; beyond a certain point, increases may not raise the killing rate much at all. Sometimes an agent is more effective at lower concentrations. For example, 70% ethanol is more effective than 95% ethanol because its activity is enhanced by the presence of water.

4. Duration of exposure. The longer a population is exposed to a microbicidal agent, the more organisms are killed (figure 7.1). To achieve sterilization, an exposure duration sufficient to reduce the probability of survival to 10–6 or less should be used.

5. Temperature. An increase in the temperature at which a chemical acts often enhances its activity. Frequently a lower concentration of disinfectant or sterilizing agent can be used at a higher temperature.

6. Local environment. The population to be controlled is not isolated but surrounded by environmental factors that may either offer protection or aid in its destruction.

For example, because heat kills more readily at an acid pH, acid foods and beverages such as fruits and tomatoes are easier to pasteurize than foods with higher pHs like milk. A second important environmental factor is organic matter that can protect microorganisms against heating and chemical disinfectants. Biofilms are a good example.

The organic matter in a surface biofilm will protect the biofilm’s microorganisms; furthermore, the biofilm and its microbes often will be hard to remove. It may be necessary to clean an object before it is disinfected or sterilized. Syringes and medical or dental equipment should be cleaned before sterilization because the presence of too much organic matter could protect pathogens and increase the risk of infection.

The same care must

be taken when pathogens are destroyed during the preparation of drinking water.

When a city’s water supply has a high content of organic material, more

chlorine must be added to disinfect it.

The Use of

Physical Methods in Control

Heat

and other physical agents are normally used to control microbial growth and

sterilize objects, as can be seen from the continual operation of the autoclave

in every microbiology laboratory. The four most frequently employed physical

agents are heat, low temperatures, filtration, and radiation.

Heat

Fire

and boiling water have been used for sterilization and disinfection since the

time of the Greeks, and heating is still one of the most popular ways to

destroy microorganisms. Either moist or dry heat may be applied.

Moist

heat readily kills viruses, bacteria, and fungi (table 7.2). Exposure to

boiling water for 10 minutes is sufficient to destroy vegetative cells and

eucaryotic spores. Unfortunately the temperature of boiling water (100°C or

212°F) is not high enough to destroy bacterial endospores that may survive hours

of boiling.

Therefore

boiling can be used for disinfection of drinking water and objects not harmed

by water, but boiling does not sterilize.

Because

heat is so useful in controlling microorganisms, it is essential to have a

precise measure of the heat-killing efficiency.

Initially

effectiveness was expressed in terms of thermal death point (TDP), the lowest

temperature at which a microbial suspension is killed in 10 minutes. Because

TDP implies that a certain temperature is immediately lethal despite the

conditions, thermal death time (TDT) is now more commonly used. This is the

shortest time needed to kill all organisms in a microbial suspension at a

specific temperature and under defined conditions.

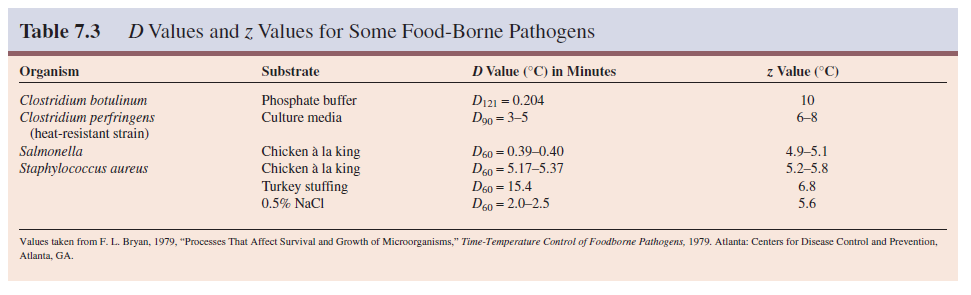

However, such destruction is logarithmic, and it is theoretically not possible to “completely destroy” microorganisms in a sample, even with extended heating. Therefore an even more precise figure, the decimal reduction time (D) or D value has gained wide acceptance. The decimal reduction time is the time required to kill 90% of the microorganisms or spores in a sample at a specified temperature. In a semilogarithmic plot of the population remaining versus the time of heating (figure 7.1), the D value is the time required for the line to drop by one log cycle or tenfold.

The D value is usually

written with a subscript, indicating the temperature for which it applies. D

values are used to estimate the relative resistance of a microorganism to

different temperatures through calculation of the z value. The z value

is the increase in temperature required to reduce D to 1/10 its value or

to reduce it by one log cycle when log D is plotted against temperature

(figure 7.2). Another way to describe heating effectiveness is with the F value.

The F value is the time in minutes at a specific temperature (usually

250°F or 121.1°C) needed to kill a population of cells or spores.

The food processing industry makes extensive use of D and z values. After a food has been canned, it must be heated to eliminate the risk of botulism arising from Clostridium botulinum spores. Heat treatment is carried out long enough to reduce a population of 1012 C. botulinum spores to 100 (one spore); thus there is a very small chance of any can having a viable spore. The D value for these spores at 121°C is 0.204 minutes.

Therefore it would take 12D or 2.5 minutes to reduce 1012 spores to one spore by heating at 121°C. The z value for C. botulinum spores is 10°C—that is, it takes a 10°C change in temperature to alter the D value tenfold. If the cans were to be processed at 111°C rather than at 121°C, the D value would increase by tenfold to 2.04 minutes and the 12D value to 24.5 minutes. D values and z values for some common food-borne pathogens are given in table 7.3. Three D values are included for Staphylococcus aureus to illustrate the variation of killing rate with environment and the protective effect of organic material.

Moist heat sterilization must be carried out at temperatures above 100°C in order to destroy bacterial endospores, and this requires the use of saturated steam under pressure. Steam sterilization is carried out with an autoclave (figure 7.3), a device somewhat like a fancy pressure cooker. The development of the autoclave by Chamberland in 1884 tremendously stimulated the growth of microbiology. Water is boiled to produce steam, which is released through the jacket and into the autoclave’s chamber.

The air initially present in the chamber is forced out until the chamber is

filled with saturated steam and the outlets are closed. Hot, saturated steam

continues to enter until the chamber reaches the desired temperature and

pressure, usually 121°C and 15 pounds of pressure.

At

this temperature saturated steam destroys all vegetative cells and endospores

in a small volume of liquid within 10 to 12 minutes. Treatment is continued for

about 15 minutes to provide a margin of safety. Of course, larger containers of

liquid such as flasks and carboys will require much longer treatment times.

|

Moist

heat is thought to kill so effectively by degrading nucleic acids and by

denaturing enzymes and other essential proteins.

It also may disrupt cell membranes. Autoclaving must be carried out properly or the processed materials will not be sterile. If all air has not been flushed out of the chamber, it will not reach 121°C even though it may reach a pressure of 15 pounds. The chamber should not be packed too tightly because the steam needs to circulate freely and contact everything in the autoclave.

Bacterial endospores

will be killed only if they are kept at 121°C for 10 to 12 minutes. When a

large volume of liquid must be sterilized, an extended sterilization time will

be needed because it will take longer for the center of the liquid to reach

121°C; 5 liters of liquid may require about 70 minutes.

In view of these potential difficulties, a biological indicator is often autoclaved along with other material. This indicator commonly consists of a culture tube containing a sterile ampule of medium and a paper strip covered with spores of Bacillus stearothermophilus or Clostridium PA3679. After autoclaving, the ampule is aseptically broken and the culture incubated for several days.

If the test bacterium does not grow in the medium, the

sterilization run has been successful. Sometimes either special tape that

spells out the word sterile or a paper indicator strip that changes

color upon sufficient heating is autoclaved with a load of material. If the

word appears on the tape or if the color changes after autoclaving, the

material is supposed to be sterile.

These approaches are convenient and save time but are not as reliable as the use of bacterial endospores. Many substances, such as milk, are treated with controlled heating at temperatures well below boiling, a process known as pasteurization in honor of its developer Louis Pasteur. In the 1860s the French wine industry was plagued by the problem of wine spoilage, which made wine storage and shipping difficult.

Pasteur examined spoiled wine under the microscope and detected microorganisms that looked like the bacteria responsible for lactic acid and acetic acid fermentations. He then discovered that a brief heating at 55 to 60°C would destroy these microorganisms and preserve wine for long periods. In 1886 the German chemists V. H. and F. Soxhlet adapted the technique for preserving milk and reducing milk transmissible diseases.

Milk pasteurization

was introduced into the United States in 1889. Milk, beer, and many other

beverages are now pasteurized. Pasteurization does not sterilize a beverage,

but it does kill any pathogens present and drastically slows spoilage by

reducing the level of nonpathogenic spoilage microorganisms.

Milk

can be pasteurized in two ways. In the older method the milk is held at 63°C

for 30 minutes. Large quantities of milk are now usually subjected to flash

pasteurization or high-temperature short-term (HTST) pasteurization, which

consists of quick heating to about 72°C for 15 seconds, then rapid cooling. The

dairy industry also sometimes uses ultrahigh-temperature (UHT) sterilization. Milk

and milk products are heated at 140 to 150°C for 1 to 3 seconds. UHT-processed

milk does not require refrigeration and can be stored at room temperature for

about 2 months without flavor changes. The small coffee creamer portions provided

by restaurants often are prepared using UHT sterilization.

Many objects are best sterilized in the absence of water by dry heat sterilization. The items to be sterilized are placed in an oven at 160 to 170°C for 2 to 3 hours. Microbial death apparently results from the oxidation of cell constituents and denaturation of proteins. Although dry air heat is less effective than moist heat— Clostridium botulinum spores are killed in 5 minutes at 121°C by moist heat but only after 2 hours at 160°C with dry heat—it has some definite advantages.

Dry heat does not corrode glassware and metal instruments as moist

heat does, and it can be used to sterilize powders, oils, and similar items.

Most laboratories sterilize glass petri dishes and pipettes with dry heat. Despite

these advantages, dry heat sterilization is slow and not suitable for heat sensitive

materials like many plastic and rubber items.

Low

Temperatures

Although

our emphasis is on the destruction of microorganisms, often the most convenient

control technique is to inhibit their growth and reproduction by the use of

either freezing or refrigeration.

This

approach is particularly important in food microbiology. Freezing items at -20°C

or lower stops microbial growth because of the low temperature and the absence

of liquid water. Some microorganisms will be killed by ice crystal disruption

of cell membranes, but freezing does not destroy contaminating microbes. In

fact, freezing is a very good method for long-term storage of microbial samples

when carried out properly, and many laboratories have a low-temperature freezer

for culture storage at -30 or -70°C. Because frozen food can contain many

microorganisms, it should be prepared and consumed promptly after thawing in

order to avoid spoilage and pathogen growth.

Refrigeration

greatly slows microbial growth and reproduction, but does not halt it

completely. Fortunately most pathogens are mesophilic and do not grow well at

temperatures around 4°C.

Refrigerated

items may be ruined by growth of psychrophilic and psychrotrophic

microorganisms, particularly if water is present.

Thus

refrigeration is a good technique only for shorter-term storage of food and

other items.

Filtration

Filtration is an excellent way to reduce the microbial population in solutions of heat-sensitive material, and sometimes it can be used to sterilize solutions. Rather than directly destroying contaminating microorganisms, the filter simply removes them. There are two types of filters. Depth filters consist of fibrous or granular materials that have been bonded into a thick layer filled with twisting channels of small diameter.

The solution containing microorganisms is

sucked through this layer under vacuum, and microbial cells are removed by

physical screening or entrapment and also by adsorption to the surface of the

filter material. Depth filters are made of diatomaceous earth (Berkefield

filters), unglazed porcelain (Chamberlain filters), asbestos, or other similar

materials.

Membrane

filters have replaced depth filters for many purposes. These circular filters

are porous membranes, a little over 0.1 mm thick, made of cellulose acetate,

cellulose nitrate, polycarbonate, polyvinylidene fluoride, or other synthetic

materials.

Although

a wide variety of pore sizes are available, membranes with pores about 0.2 µm

in diameter are used to remove most vegetative cells, but not viruses, from

solutions ranging in volume from 1 ml to many liters. The membranes are held in

special holders (figure 7.4) and often preceded by depth filters made of glass fibers

to remove larger particles that might clog the membrane filter.

The

solution is pulled or forced through the filter with a vacuum or with pressure

from a syringe, peristaltic pump, or nitrogen gas bottle, and collected in

previously sterilized containers. Membrane filters remove microorganisms by

screening them out much as a sieve separates large sand particles from small

ones (figure 7.5).

These

filters are used to sterilize pharmaceuticals, ophthalmic solutions, culture

media, oils, antibiotics, and other heat-sensitive solutions.

Air also can be sterilized by filtration. Two common examples are surgical masks and cotton plugs on culture vessels that let air in but keep microorganisms out. Laminar flow biological safety cabinets employing high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, which remove 99.97% of 0.3 µm particles, are one of the most important air filtration systems. Laminar flow biological safety cabinets force air through HEPA filters, then project a vertical curtain of sterile air across the cabinet opening.

This protects a worker from microorganisms being handled

within the cabinet and prevents contamination of the room (figure 7.6). A person

uses these cabinets when working with dangerous agents such as Mycobacterium

tuberculosis, tumor viruses, and recombinant DNA. They are also employed in

research labs and industries, such as the pharmaceutical industry, when a

sterile working surface is needed for conducting assays, preparing media,

examining tissue cultures, and the like.

Radiation

The

types of radiation and the ways in which radiation damages or destroys

microorganisms have already been discussed. The practical uses of ultraviolet

and ionizing radiation in sterilizing objects are briefly described next.

Ultraviolet

(UV) radiation around 260 nm (see figure 6.17) is quite lethal but does

not penetrate glass, dirt films, water, and other substances very effectively.

Because of this disadvantage, UV radiation is used as a sterilizing agent only

in a few specific situations.

UV

lamps are sometimes placed on the ceilings of rooms or in biological safety

cabinets to sterilize the air and any exposed surfaces.

Because

UV radiation burns the skin and damages eyes, people working in such areas must

be certain the UV lamps are off when the areas are in use. Commercial UV units

are available for water treatment. Pathogens and other microorganisms are

destroyed when a thin layer of water is passed under the lamps.

Ionizing radiation is an excellent sterilizing agent and penetrates deep into objects. It will destroy bacterial endospores and vegetative cells, both procaryotic and eucaryotic; however, ionizing radiation is not always as effective against viruses. Gamma radiation from a cobalt 60 source is used in the cold sterilization of antibiotics, hormones, sutures, and plastic disposable supplies such as syringes. Gamma radiation has also been used to sterilize and “pasteurize” meat and other food.

Irradiation can eliminate the threat of such pathogens as Escherichia coli O157:H7, Staphylococcus aureus, and Campylobacter jejuni. Both the Food and Drug Administration and the World Health Organization have approved food irradiation and declared it safe. A commercial irradiation plant operates near Tampa, Florida.

However, this process has not yet been widely employed in

the United States because of the cost and concerns about the effects of gamma

radiation on food. The U.S. government currently approves the use of radiation

to treat poultry, beef, pork, veal, lamb, fruits, vegetables, and spices. It

will probably be more extensively employed in the future.

The Use of

Chemical Agents in Control

Although

objects are sometimes disinfected with physical agents, chemicals are more

often employed in disinfection and antisepsis.

Many

factors influence the effectiveness of chemical disinfectants and antiseptics

as previously discussed. Factors such as the kinds of microorganisms

potentially present, the concentration and nature of the disinfectant to be

used, and the length of treatment should be considered. Dirty surfaces must be

cleaned before a disinfectant or antiseptic is applied. The proper use of chemical

agents is essential to laboratory and hospital safety (Box 7.2; see also Box

36.1). It should be noted that chemicals also are employed to prevent

microbial growth in food. This is discussed in the chapter on food microbiology.

Many

different chemicals are available for use as disinfectants, and each has its

own advantages and disadvantages. In selecting an agent, it is important to

keep in mind the characteristics of a desirable disinfectant. Ideally the

disinfectant must be effective against a wide variety of infectious agents

(gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, acid-fast bacteria, bacterial

endospores, fungi, and viruses) at high dilutions and in the presence of

organic matter.

Although

the chemical must be toxic for infectious agents, it should not be toxic to

people or corrosive for common materials. In practice, this balance between

effectiveness and low toxicity for animals is hard to achieve. Some chemicals are

used despite their low effectiveness because they are relatively nontoxic. The

disinfectant should be stable upon storage, odorless or with a pleasant odor,

soluble in water and lipids

for

penetration into microorganisms, and have a low surface tension so that it can

enter cracks in surfaces. If possible the disinfectant should be relatively

inexpensive.

One

potentially serious problem is the overuse of triclosan and other germicides.

This antibacterial agent is now found in products such as deodorants,

mouthwashes, soaps, cutting boards, and baby toys. Triclosan seems to be

everywhere. Unfortunately we are already seeing the emergence of

triclosan-resistant bacteria.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa actively pumps the antiseptic out the cell. Bacteria

seem to be responding to antiseptic overuse in the same way as they reacted to

antibiotic overuse. There is now some evidence that extensive use of triclosan

also increases the frequency of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Thus overuse

of antiseptics can have unintended harmful consequences.

The properties and uses of several groups of common disinfectants and antiseptics are surveyed next. Many of their characteristics are summarized in tables 7.4 and 7.5. Structures of some common agents are given in figure 7.7.

Phenolics

Phenol

was the first widely used antiseptic and disinfectant. In 1867 Joseph Lister

employed it to reduce the risk of infection during operations. Today phenol and

phenolics (phenol derivatives) such as cresols, xylenols, and orthophenylphenol

are used as disinfectants in laboratories and hospitals. The commercial

disinfectant Lysol is made of a mixture of phenolics.

Phenolics

act by denaturing proteins and disrupting cell membranes. They have some real

advantages as disinfectants: phenolics are tuberculocidal, effective in the

presence of organic material, and remain active on surfaces long after

application.

However,

they do have a disagreeable odor and can cause skin irritation. Hexachlorophene

(figure 7.7) has been one of the most popular antiseptics because it persists

on the skin once applied and reduces skin bacteria for long periods. However,

it can cause brain damage and is now used in hospital nurseries only in

response to a staphylococcal outbreak.

Alcohols

Alcohols

are among the most widely used disinfectants and antiseptics. They are bactericidal

and fungicidal but not sporicidal; some lipid-containing viruses are also

destroyed. The two most popular alcohol germicides are ethanol and isopropanol,

usually used in about 70 to 80% concentration. They act by denaturing proteins

and possibly by dissolving membrane lipids. A 10 to 15 minute soaking is

sufficient to disinfect thermometers and small instruments.

Halogens

A halogen is any of the five elements (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, and astatine) in group VIIA of the periodic table. They exist as diatomic molecules in the free state and form salt-like compounds with sodium and most other metals. The halogens iodine and chlorine are important antimicrobial agents. Iodine is used as a skin antiseptic and kills by oxidizing cell constituents and iodinating cell proteins.

At higher concentrations, it may even kill some

spores. Iodine often has been applied as tincture of iodine, 2% or more iodine in

a water-ethanol solution of potassium iodide. Although it is an effective antiseptic,

the skin may be damaged, a stain is left, and iodine allergies can result. More

recently iodine has been complexed with an organic carrier to form an iodophor.

Iodophors are water soluble, stable, and non staining, and release iodine

slowly to minimize skin burns and irritation. They are used in hospitals for

preoperative skin degerming and in hospitals and laboratories for disinfecting.

Some

popular brands are Wescodyne for skin and laboratory disinfection and Betadine

for wounds.

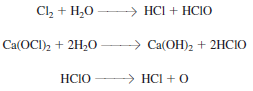

Chlorine

is the usual disinfectant for municipal water supplies and swimming pools and

is also employed in the dairy and food industries. It may be applied as

chlorine gas, sodium hypochlorite, or calcium hypochlorite, all of which yield

hypochlorous acid (HClO) and then atomic oxygen. The result is oxidation of

cellular materials and destruction of vegetative bacteria and fungi, although

not spores.

Death of almost all microorganisms usually occurs within 30 minutes. Since organic material interferes with chlorine action by reacting with chlorine and its products, an excess of chlorine is added to ensure microbial destruction. One potential problem is that chlorine reacts with organic compounds to form carcinogenic trihalomethanes, which must be monitored in drinking water. Ozone sometimes has been used successfully as an alternative to chlorination in Europe and Canada.

Municipal water purification Chlorine is also an excellent disinfectant

for individual use because it is effective, inexpensive, and easy to employ. Small

quantities of drinking water can be disinfected with halazone tablets. Halazone

(parasulfone dichloramidobenzoic acid) slowly releases chloride when added to

water and disinfects it in about a half hour. It is frequently used by campers

lacking access to uncontaminated drinking water.

Chlorine

solutions make very effective laboratory and household disinfectants. An

excellent disinfectant-detergent combination can be prepared if a 1/100

dilution of household bleach (e.g., 1.3 fl oz of Clorox or Purex bleach in 1

gal or 10 ml/liter) is combined with sufficient nonionic detergent (about 1

oz/gal or 7.8 ml/liter) to give a 0.8% detergent concentration. This mixture

will remove both dirt and bacteria.

Heavy Metals

For

many years the ions of heavy metals such as mercury, silver, arsenic, zinc, and

copper were used as germicides. More recently these have been superseded by

other less toxic and more effective germicides

(many heavy metals are more bacteriostatic than bactericidal).

There

are a few exceptions. A 1% solution of silver nitrate is often added to the

eyes of infants to prevent ophthalmic gonorrhea (in many hospitals,

erythromycin is used instead of silver nitrate because it is effective against Chlamydia

as well as Neisseria). Silver sulfadiazine is used on burns. Copper

sulfate is an effective algicide in lakes and swimming pools.

Heavy

metals combine with proteins, often with their sulfhydryl groups, and

inactivate them. They may also precipitate cell proteins.

Quaternary

Ammonium Compounds

Detergents

[Latin detergere, to wipe off or away] are organic molecules that serve

as wetting agents and emulsifiers because they have both polar hydrophilic and

nonpolar hydrophobic ends. Due to their amphipathic nature, detergents

solubilize otherwise insoluble residues and are very effective cleansing agents.

They are different than soaps, which are derived from fats.

Although

anionic detergents have some antimicrobial properties, only cationic detergents

are effective disinfectants.

The

most popular of these disinfectants are quaternary ammonium compounds

characterized by a positively charged quaternary nitrogen and a long

hydrophobic aliphatic chain (figure 7.7). They disrupt microbial membranes and

may also denature proteins.

Cationic

detergents like benzalkonium chloride and cetylpyridinium chloride kill most

bacteria but not M. tuberculosis or endospores.

They

do have the advantages of being stable, nontoxic, and bland but they are

inactivated by hard water and soap. Cationic detergents are often used as

disinfectants for food utensils and small instruments and as skin antiseptics.

Several brands are on the market. Zephiran contains benzalkonium chloride and

Ceepryn, cetylpyridinium chloride.

Aldehydes

Both

of the commonly used aldehydes, formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, are highly

reactive molecules that combine with nucleic

acids

and proteins and inactivate them, probably by crosslinking and alkylating

molecules (figure 7.7). They are sporicidal and can be used as chemical

sterilants. Formaldehyde is usually dissolved in water or alcohol before use. A

2% buffered solution of glutaraldehyde is an effective disinfectant. It is less

irritating than formaldehyde and is used to disinfect hospital and laboratory

equipment. Glutaraldehyde usually disinfects objects within about 10 minutes

but may require as long as 12 hours to destroy all spores.

Sterilizing Gases

Many

heat-sensitive items such as disposable plastic petri dishes and syringes,

heart-lung machine components, sutures, and catheters are now sterilized with

ethylene oxide gas (figure 7.7). Ethylene oxide (EtO) is both microbicidal and

sporicidal and kills by combining with cell proteins. It is a particularly effective

sterilizing agent because it rapidly penetrates packing materials, even plastic

wraps.

Sterilization

is carried out in a special ethylene oxide sterilizer, very much resembling an

autoclave in appearance, that controls the EtO concentration, temperature, and

humidity. Because pure EtO is explosive, it is usually supplied in a 10 to 20% concentration

mixed with either CO2 or dichlorodifluoromethane.

The

ethylene oxide concentration, humidity, and temperature influence the rate of

sterilization. A clean object can be sterilized if treated for 5 to 8 hours at

38°C or 3 to 4 hours at 54°C when the relative humidity is maintained at 40 to

50% and the EtO concentration at 700 mg/liter. Extensive aeration of the

sterilized materials is necessary to remove residual EtO because it is so

toxic.

Betapropiolactone

(BPL) is occasionally employed as a sterilizing gas. In the liquid form it has

been used to sterilize vaccines and sera. BPL decomposes to an inactive form

after several hours and is therefore not as difficult to eliminate as EtO. It

also destroys microorganisms more readily than ethylene oxide but does not

penetrate materials well and may be carcinogenic. For these reasons, BPL has

not been used as extensively as EtO.

Recently

vapor-phase hydrogen peroxide has been used to decontaminate biological safety

cabinets.

Evaluation of Antimicrobial Agent Effectiveness

Testing of

antimicrobial agents is a complex process regulated by two different federal

agencies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates disinfectants,

whereas agents used on humans and animals are under the control of the Food and

Drug Administration.

Testing of

antimicrobial agents often begins with an initial screening test to see if they

are effective and at what concentrations.

This may be

followed by more realistic in-use testing. The best-known disinfectant

screening test is the phenol coefficient test in which the potency of a

disinfectant is compared with that of phenol. A series of dilutions of phenol

and the experimental disinfectant are inoculated with the test bacteria Salmonella

typhi and Staphylococcus aureus, then placed in a 20 or 37°C water

bath.

These

inoculated disinfectant tubes are next subcultured to regular fresh medium at 5

minute intervals, and the subcultures are incubated for two or more days. The

highest dilutions that kill the bacteria after a 10 minute exposure, but not

after 5 minutes, are used to calculate the phenol coefficient. The reciprocal of

the appropriate test disinfectant dilution is divided by that for phenol to

obtain the coefficient. Suppose that the phenol dilution was 1/90 and maximum

effective dilution for disinfectant X was 1/450. The phenol coefficient of X

would be 5.

The higher the

phenol coefficient value, the more effective the disinfectant under these test

conditions. A value greater than 1 means that the disinfectant is more

effective than phenol. A few representative phenol coefficient values are given

in table 7.6.

The phenol

coefficient test is a useful initial screening procedure, but the phenol

coefficient can be misleading if taken as a direct indication of disinfectant

potency during normal use. This is because the phenol coefficient is determined

under carefully controlled conditions with pure bacterial strains, whereas

disinfectants are normally used on complex populations in the presence of

organic matter and with significant variations in environmental factors like

pH, temperature, and presence of salts.

To more

realistically estimate disinfectant effectiveness, other tests are often used.

The rates at which selected bacteria are destroyed with various chemical agents

may be experimentally determined and compared. A use dilution test can also be

carried out.

Stainless

steel cylinders are contaminated with specific bacterial species under

carefully controlled conditions. The cylinders are dried briefly, immersed in

the test disinfectants for 10 minutes, transferred to culture media, and

incubated for two days.

The

disinfectant concentration that kills the organisms in the sample with a 95%

level of confidence under these conditions is determined.

Disinfectants

also can be tested under conditions designed to simulate normal in-use

situations. In-use testing techniques allow a more accurate determination of

the proper disinfectant concentration for a particular situation.

No comments:

Post a Comment