In Procaryotic chapter, considerable attention is devoted to prokaryotic cell structure and function because bacteria are immensely important in microbiology and have occupied a large portion of microbiologists’ attention in the past. Nevertheless, eucaryotic algae, fungi, and protozoa also are microorganisms and have been extensively studied.

These

organisms often are extraordinarily complex, interesting in their own right,

and prominent members of the ecosystem (figure 4.1). In addition, fungi

(and to some extent, algae) are exceptionally useful in industrial microbiology.

Many fungi and protozoa are also major human pathogens; one only need think of

either malaria or African sleeping sickness to appreciate

the significance of eucaryotes in pathogenic microbiology. So, although this

text emphasizes bacteria, eucaryotic microorganisms are discussed at many

points.

This

chapter focuses on eucaryotic cell structure and its relationship to cell

function. Because many valuable studies on eukaryotic cell ultrastructure have

used organisms other than microorganisms, some work on nonmicrobial cells is

presented. At the end of the chapter, procaryotic and eucaryotic cells are

compared in some depth.

An Overview of Eucaryotic Cell Structure

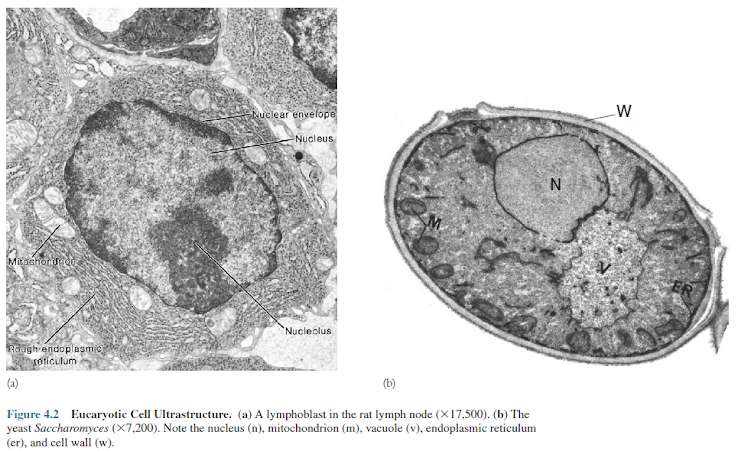

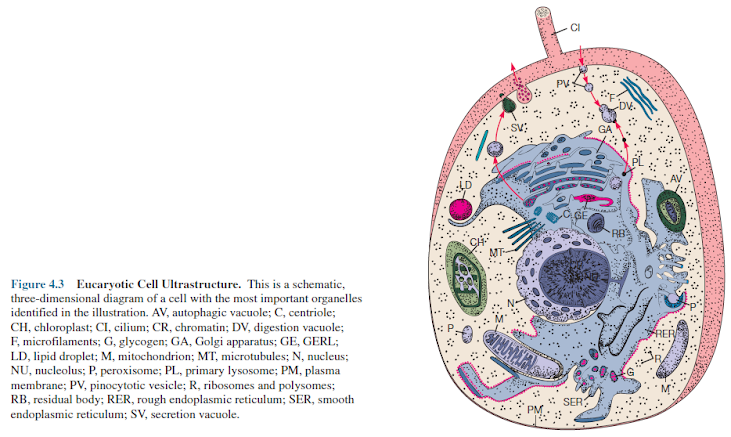

The

most obvious difference between eucaryotic and prokaryotic cells is in their

use of membranes. Eucaryotic cells have membrane delimited nuclei, and

membranes also play a prominent part in the structure of many other organelles

(figures 4.2 and 4.3).

Organelles are intracellular structures that perform specific functions in cells analogous to the functions of organs in the body. The name organelle (little organ) was coined because biologists saw a parallel between the relationship of organelles to a cell and that of organs to the whole body. It is not satisfactory to define organelles as membrane- bound structures because this would exclude such components as ribosomes and bacterial flagella. A comparison of figures 4.2 and 4.3 shows how much more structurally complex the eucaryotic cell is.

This complexity is due chiefly to the use of internal membranes for several purposes. The partitioning of the eucaryotic cell interior by membranes makes possible the placement of different biochemical and physiological functions in separate compartments so that they can more easily take place simultaneously under independent control and proper coordination.

Large

membrane surfaces make possible greater respiratory and photosynthetic activity

because these processes are located exclusively in membranes. The

intracytoplasmic membrane complex also serves as a transport system to move

materials between different cell locations. Thus abundant membrane systems probably

are necessary in eucaryotic cells because of their large volume and the need

for adequate regulation, metabolic activity, and transport.

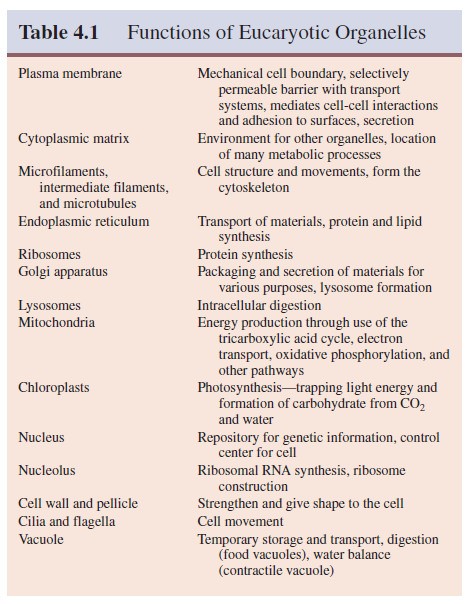

Figures

4.2, 4.3, and 4.26b provide generalized views of eukaryotic cell

structure and illustrate most of the organelles to be discussed. Table 4.1 briefly

summarizes the functions of the major eucaryotic organelles. Those organelles

lying inside the plasma membrane are first described, and then components

outside the membrane are discussed.

The Cytoplasmic Matrix, Microfilaments, Intermediate Filaments,

and Microtubules

When

a eucaryotic cell is examined at low power with the electron microscope, its

larger organelles are seen to lie in an apparently featureless, homogeneous

substance called the cytoplasmic matrix. The matrix, although

superficially uninteresting, is actually one of the most important and complex

parts of the cell. It is the “environment” of the organelles and the location

of many important biochemical processes. Several physical changes seen in cells—viscosity

changes, cytoplasmic streaming, and others—also are due to matrix activity.

Water

constitutes about 70 to 85% by weight of a eukaryotic cell. Thus a large part

of the cytoplasmic matrix is water. Cellular water can exist in two different

forms. Some of it is bulk or free water; this is normal, osmotically active

water. Osmosis, water activity, and growth Water also can exist as bound water

or water of hydration.

This

water is bound to the surface of proteins and other macromolecules and is

osmotically inactive and more ordered than bulk water. There is some evidence

that bound water is the site of many metabolic processes. The protein content

of cells is so high that the cytoplasmic matrix often may be semi-crystalline.

Usually matrix pH is around neutrality, about pH 6.8 to 7.1, but can vary widely.

For example, protozoan digestive vacuoles may reach pHs as low as 3 to 4.

Probably

all eucaryotic cells have microfilaments, minute protein filaments, 4 to

7 nm in diameter, which may be either scattered within the cytoplasmic matrix

or organized into networks and parallel arrays. Microfilaments are involved in

cell motion and shape changes. Some examples of cellular movements associated with

microfilament activity are the motion of pigment granules, amoeboid movement,

and protoplasmic streaming in slime molds.

The

participation of microfilaments in cell movement is suggested by electron

microscopic studies showing that they frequently are found at locations

appropriate for such a role. For example, they are concentrated at the interface

between stationary and flowing cytoplasm in plant cells and slime molds.

Experiments using the drug cytochalasin B have provided additional evidence.

Cytochalasin B disrupts microfilament structure and often simultaneously

inhibits cell movements. However, because the drug has additional effects in

cells, a direct cause-and-effect interpretation of these experiments is

sometimes difficult.

Microfilament

protein has been isolated and analyzed chemically. It is an actin, very similar

to the actin contractile protein of muscle tissue. This is further indirect

evidence for microfilament involvement in cell movement.

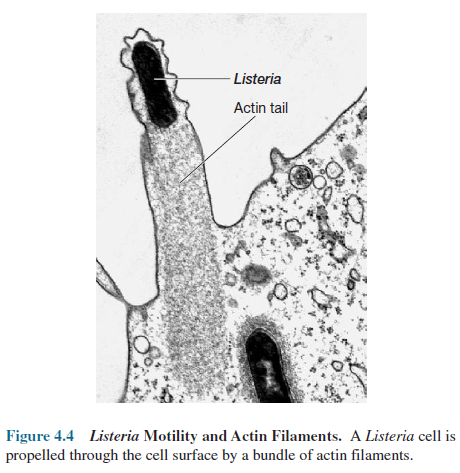

Some

pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes make use of eucaryotic actin to

move rapidly through the host cell. The ActA protein released by Listeria causes

the polymerization of actin filaments at the end of the bacterium. A tail of

actin is formed and trapped in the host cytoskeleton. Its continued elongation pushes

the bacterium along at rates up to 11 µm/minute.

The

bacterium can even be propelled through the cell surface and into neighboring

cells (figure 4.4). A second type of small filamentous organelle in the

cytoplasmic matrix is shaped like a thin cylinder about 25 nm in diameter.

Because

of its tubular nature this organelle is called a microtubule. Microtubules

are complex structures constructed of two slightly different spherical

protein subunits named tubulins, each of which is approximately 4 to 5 nm in

diameter. These subunits are assembled in a helical arrangement to form a

cylinder with an average of 13 subunits in one turn or circumference (figure

4.5).

Microtubules

serve at least three purposes:

(1) they help maintain cell shape,

(2) are involved with microfilaments in cell movements, and

(3) participate in intracellular transport processes.

Evidence for a structural role comes from their intracellular distribution and studies on the effects of the drug colchicine. Long, thin cell structures requiring support such as the axopodia (long, slender, rigid pseudopodia) of protozoa contain microtubules (figure 4.6).

When migrating embryonic nerve and

heart cells are exposed to colchicine, they simultaneously lose their

microtubules and their characteristic shapes. The shapeless cells seem to

wander aimlessly as if incapable of directed movement without their normal

form. Their microfilaments are still intact, but due to the disruption of their

microtubules by colchicine, they no longer behave normally.

Microtubules

also are present in structures that participate in cell or organelle

movements—the mitotic spindle, cilia, and flagella.

For

example, the mitotic spindle is constructed of microtubules; when a dividing

cell is treated with colchicine, the spindle is disrupted and chromosome

separation blocked. Microtubules also are essential to the movement of

eucaryotic cilia and flagella.

Other

kinds of filamentous components also are present in the matrix, the most

important of which are the intermediate filaments (about 8 to 10 nm in

diameter). The microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments are

major components of a vast, intricate network of interconnected filaments

called the cytoskeleton (figure 4.7). As mentioned previously,

the cytoskeleton plays a role in both cell shape and movement. Procaryotes lack

a true, organized cytoskeleton and may not possess actinlike proteins.

The

Endoplasmic Reticulum

Besides the cytoskeleton, the cytoplasmic matrix is permeated with an irregular network of branching and fusing membranous tubules, around 40 to 70 nm in diameter, and many flattened sacs called cisternae (s., cisterna). This network of tubules and cisternae is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (figure 4.2a and figure 4.8). The nature of the ER varies with the functional and physiological status of the cell.

In cells synthesizing a great deal of protein for purposes such as

secretion, a large part of the ER is studded on its outer surface with

ribosomes and is called rough or granular endoplasmic reticulum (RER or GER).

Other cells, such as those producing large quantities of lipids, have ER that lacks

ribosomes. This is smooth or agranular ER (SER orAER).

The

endoplasmic reticulum has many important functions. It transports proteins,

lipids, and probably other materials through the cell. Lipids and proteins are

synthesized by ER-associated enzymes and ribosomes. Polypeptide chains

synthesized on RERbound ribosomes may be inserted either into the ER membrane

or into its lumen for transport elsewhere. The ER is also a major site of cell

membrane synthesis.

New endoplasmic

reticulum is produced through expansion of the old. Many biologists think the

RER synthesizes new ER proteins and lipids. “Older” RER then loses its

connected ribosomes and is modified to become SER. Not everyone agrees with this

interpretation, and other mechanisms of growth of ER are possible.

The Golgi

Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus is a membranous organelle composed of flattened, saclike cisternae stacked on each other (figure 4.9). These membranes, like the smooth ER, lack bound ribosomes. There are usually around 4 to 8 cisternae or sacs in a stack, although there may be many more.

Each sac is 15 to 20 nm thick and

separated from other cisternae by 20 to 30 nm. A complex network of tubules and

vesicles (20 to 100 nm in diameter) is located at the edges of the cisternae.

The stack of cisternae has a definite polarity because there are two ends or

faces that are quite different from one another.

The

sacs on the cis or forming face often are associated with the ER and differ

from the sacs on the trans or maturing face in thickness, enzyme content, and

degree of vesicle formation. It appears that material is transported from cis

to trans cisternae by vesicles that bud off the cisternal edges and move to the

next sac.

The

Golgi apparatus is present in most eucaryotic cells, but many fungi and ciliate

protozoa may lack a well-formed structure.

Sometimes

it consists of a single stack of cisternae; however, many cells may contain up

to 20, and sometimes more, separate stacks. These stacks of cisternae, often

called dictyosomes, can be clustered in one region or scattered about the cell.

The Golgi apparatus packages materials and prepares them for secretion, the

exact nature of its role varying with the organism.

The

surface scales of some flagellated algae and radiolarian protozoa appear to be

constructed within the Golgi apparatus and then transported to the surface in

vesicles. It often participates in the development of cell membranes and in the

packaging of cell products. The growth of some fungal hyphae occurs when Golgi

vesicles contribute their contents to the wall at the hyphal tip.

In

all these processes, materials move from the ER to the Golgi apparatus. Most

often vesicles bud off the ER, travel to the Golgi apparatus, and fuse with the

cis cisternae. Thus the Golgi apparatus is closely related to the ER in both a

structural and a functional sense. Most proteins entering the Golgi apparatus

from the ER are glycoproteins containing short carbohydrate chains.

The

Golgi apparatus frequently modifies proteins destined for different fates by

adding specific groups and then sends the proteins on their way to the proper

location (e.g., lysosomal proteins have phosphates added to their mannose

sugars).

Lysosomes and

Endocytosis

A very important function of the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum is the synthesis of another organelle, the lysosome. This organelle (or a structure very much like it) is found in a variety of microorganisms—protozoa, some algae, and fungi—as well as in plants and animals. Lysosomes are roughly spherical and enclosed in a single membrane; they average about 500 nm in diameter, but range from 50 nm to several µm in size. They are involved in intracellular digestion and contain the enzymes needed to digest all types of macromolecules. These enzymes, called hydrolases, catalyze the hydrolysis of molecules and function best under slightly acid conditions (usually around pH 3.5 to 5.0). Lysosomes maintain an acidic environment by pumping protons into their interior.

Digestive

enzymes are manufactured by the RER and packaged to form lysosomes by the Golgi

apparatus. A segment of smooth ER near the Golgi apparatus also may bud off

lysosomes.

Lysosomes

are particularly important in those cells that obtain nutrients through

endocytosis. In this process a cell takes up solutes or particles by enclosing

them in vacuoles and vesicles pinched off from its plasma membrane. Vacuoles

and vesicles are membrane delimited cavities that contain fluid, and often

solid material. Larger cavities will be called vacuoles, and smaller cavities,

vesicles. There are two major forms of endocytosis: phagocytosis and

pinocytosis.

During

phagocytosis large particles and even other microorganisms are enclosed in a

phagocytic vacuole or phagosome and engulfed (figure 4.10a). In

pinocytosis small amounts of the surrounding liquid with its solute molecules

are pinched off as tiny pinocytotic vesicles (also called pinocytic vesicles)

or pinosomes. Often phagosomes and pinosomes are collectively called endosomes

because they are formed by endocytosis. The type of pinocytosis, receptor mediated

endocytosis, that produces coated vesicles is important in the entry of animal

viruses into host cells.

Material

in endosomes is digested with the aid of lysosomes. Newly formed lysosomes, or primary

lysosomes, fuse with phagocytic vacuoles to yield secondary lysosomes, lysosomes

with material being digested (figure 4.10). These phagocytic vacuoles or

secondary lysosomes often are called food vacuoles. Digested nutrients then

leave the secondary lysosome and enter the cytoplasm. When the lysosome has

accumulated large quantities of indigestible material, it is known as a residual

body.

Lysosomes

join with phagosomes for defensive purposes as well as to acquire nutrients.

Invading bacteria, ingested by a phagocytic cell, usually are destroyed when

lysosomes fuse with the phagosome. This is commonly seen in leukocytes (white

blood cells) of vertebrates.

Cells

can selectively digest portions of their own cytoplasm in a type of secondary

lysosome called an autophagic vacuole (figure 4.10a). It is

thought that these arise by lysosomal engulfment of a piece of cytoplasm (figure

4.11), or when the ER pinches off cytoplasm to form a vesicle that

subsequently fuses with lysosomes. Autophagy probably plays a role in the

normal turnover or recycling of cell constituents. A cell also can survive a

period of starvation by selectively digesting portions of itself to remain

alive. Following cell death, lysosomes aid in digestion and removal of cell

debris.

A

most remarkable thing about lysosomes is that they accomplish all these tasks

without releasing their digestive enzymes into the cytoplasmic matrix, a

catastrophe that would destroy the cell. The lysosomal membrane retains

digestive enzymes and other macromolecules while allowing small digestion products

to leave.

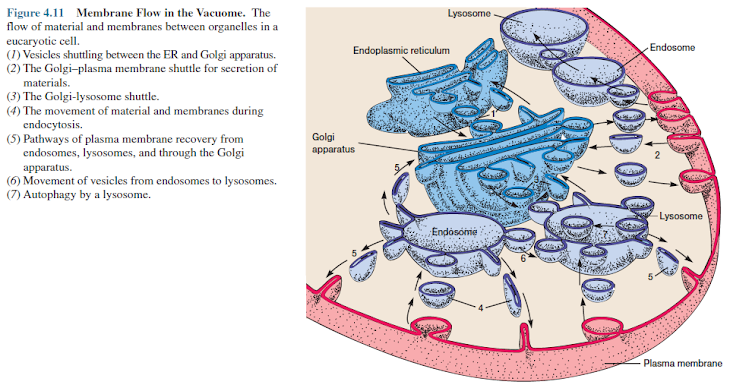

The

intricate complex of membranous organelles composed of the Golgi apparatus,

lysosomes, endosomes, and associated structures seems to operate as a coordinated

whole whose main function is the import and export of materials (figure 4.11).

Christian de Duve (Nobel Prize, 1974) has suggested that this complex be called

the vacuome in recognition of its functional unity. The ER manufactures

secretory proteins and membrane, and contributes these to the Golgi apparatus.

The

Golgi apparatus then forms secretory vesicles that fuse with the plasma

membrane and release material to the outside. It also produces lysosomes that

fuse with endosomes to digest material acquired through phagocytosis and

pinocytosis.

Membrane

movement in the region of the vacuome lying between the Golgi apparatus and the

plasma membrane is two-way. Empty vesicles often are recycled and returned to

the Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane rather than being destroyed.

These

exchanges in the vacuome occur without membrane rupture so that vesicle

contents never escape directly into the cytoplasmic matrix.

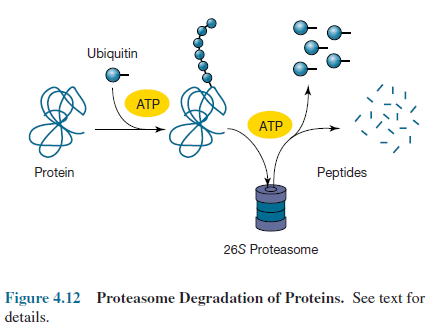

More

recently a nonlysosomal protein degradation system has been discovered in

eucaryotic cells, a few bacteria, and many archaea. The majority of eucaryotic

proteins may be degraded by this system. In eucaryotes, proteins are targeted

for destruction by the attachment of several small ubiquitin polypeptides (figure

4.12). The marked protein then enters a huge cylindrical complex called a

26S proteasome, where it is degraded to peptides in an ATP-dependent

process and the ubiquitins are released. The peptides may be hydrolyzed to

amino acids. In this case the system is being used to recycle proteins. The

proteasome also is involved in producing peptides for antigen presentation

during many immunological responses.

Eucaryotic Ribosomes

The

eucaryotic ribosome can either be associated with the endoplasmic reticulum or

be free in the cytoplasmic matrix and is larger than the bacterial 70S

ribosome. It is a dimer of a 60S and a 40S subunit, about 22 nm in diameter,

and has a sedimentation coefficient of 80S and a molecular weight of 4 million.

When bound to the endoplasmic reticulum to form rough ER, it is attached through

its 60S subunit.

Both

free and RER-bound ribosomes synthesize proteins. As mentioned earlier,

proteins made on the ribosomes of the RER either enter its lumen for transport,

and often for secretion, or are inserted into the ER membrane as integral

membrane proteins.

Free

ribosomes are the sites of synthesis for nonsecretory and nonmembrane proteins.

Some proteins synthesized by free ribosomes are inserted into organelles such

as the nucleus, mitochondrion, and chloroplast. Molecular chaperones aid the

proper folding of proteins after synthesis. They also assist the transport of

proteins into eucaryotic organelles such as mitochondria. Several ribosomes usually

attach to a single messenger RNA and simultaneously translate its message into

protein. These complexes of messenger RNA and ribosomes are called polyribosomes

or polysomes. Ribosomal participation in protein synthesis is dealt with

later.

Mitochondria

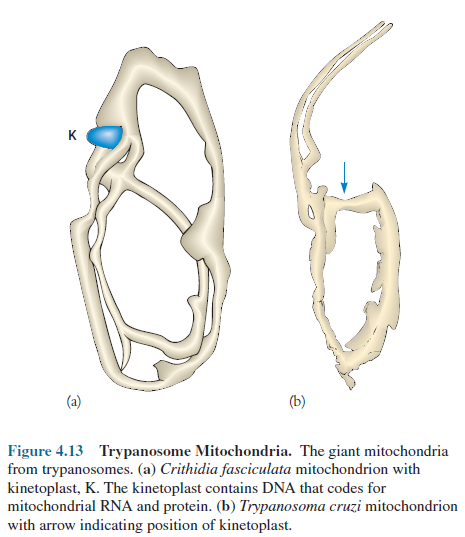

Found

in most eucaryotic cells, mitochondria (s., mitochondrion) frequently

are called the “powerhouses” of the cell. Tricarboxylic acid cycle activity and

the generation of ATP by electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation take

place here. In the transmission electron microscope, mitochondria usually are cylindrical

structures and measure approximately 0.3 to 1.0 µm by 5 to 10 µm. (In other

words, they are about the same size as bacterial cells.) Although cells can

possess as many as 1,000 or more mitochondria, at least a few cells (some

yeasts, unicellular algae, and trypanosome protozoa) have a single giant

tubular mitochondrion twisted into a continuous network permeating the cytoplasm

(figure 4.13).

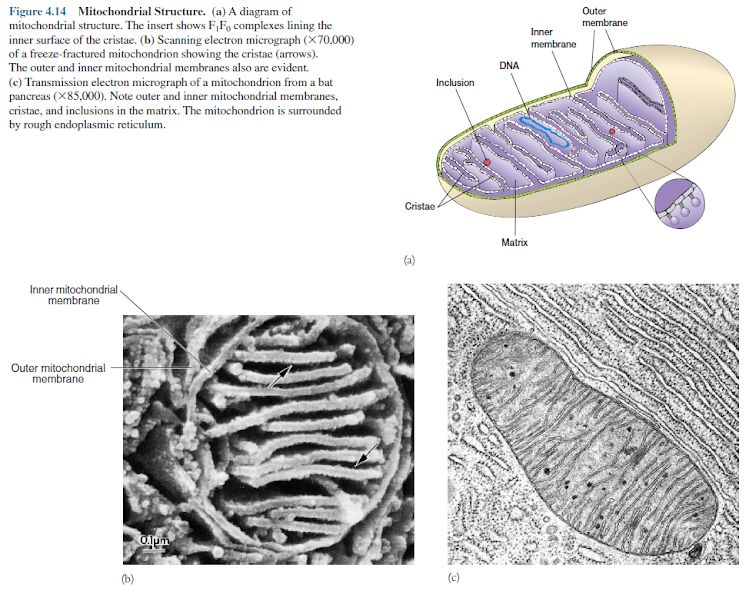

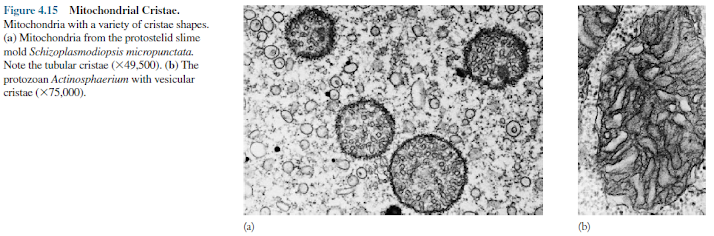

The

mitochondrion is bounded by two membranes, an outer mitochondrial membrane

separated from an inner mitochondrial membrane by a 6 to 8 nm intermembrane

space (figure 4.14). Special infoldings of the inner membrane, called cristae

(s., crista), greatly increase its surface area. Their shape differs

in mitochondria from various species. Fungi have plate-like (laminar) cristae, whereas

euglenoid flagellates may have cristae shaped like disks.

Tubular

cristae are found in a variety of eucaryotes; however, amoebae can possess

mitochondria with cristae in the shape of vesicles (figure 4.15). The

inner membrane encloses the mitochondrial matrix, a dense matrix containing

ribosomes, DNA, and often large calcium phosphate granules. Mitochondrial

ribosomes are smaller than cytoplasmic ribosomes and resemble those of bacteria

in several ways, including their size and subunit composition.

Mitochondrial

DNA is a closed circle like bacterial DNA. Each mitochondrial compartment is

different from the others in chemical and enzymatic composition. The outer and

inner mitochondrial membranes, for example, possess different lipids. Enzymes and

electron carriers involved in electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation

(the formation of ATP as a consequence of electron transport) are located only

in the inner membrane. The enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the β-oxidation

pathway for fatty acids are located in the matrix.

The

inner membrane of the mitochondrion has another distinctive structural feature

related to its function. Many small spheres, about 8.5 nm diameter, are

attached by stalks to its inner surface. The spheres are called F1 particles

and synthesize ATP during cellular respiration.

The

mitochondrion uses its DNA and ribosomes to synthesize some of its own

proteins. In fact, mutations in mitochondrial DNA often lead to serious

diseases in humans. Most mitochondrial proteins, however, are manufactured

under the direction of the nucleus. Mitochondria reproduce by binary fission.

Chloroplasts show similar partial independence and reproduction by binary fission.

Because both organelles resemble bacteria to some extent, it has been suggested

that these organelles arose from symbiotic associations between bacteria and

larger cells (Box 4.1).

Chloroplasts

Plastids

are cytoplasmic organelles of algae and higher plants that often possess pigments

such as chlorophylls and carotenoids, and are the sites of synthesis and

storage of food reserves.

The

most important type of plastid is the chloroplast. Chloroplasts contain

chlorophyll and use light energy to convert CO2 and water to

carbohydrates and O2. That is, they are the site of photosynthesis.

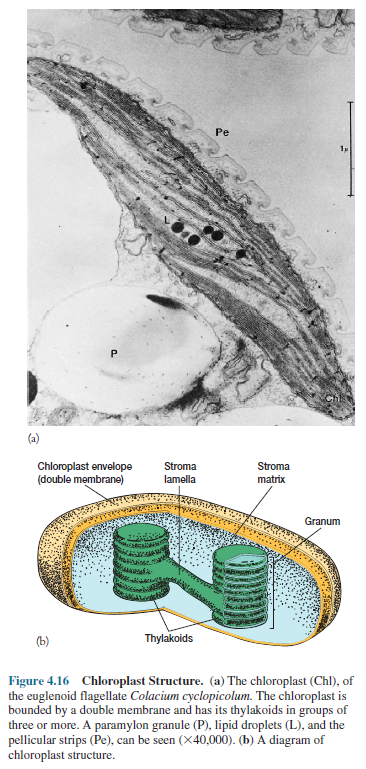

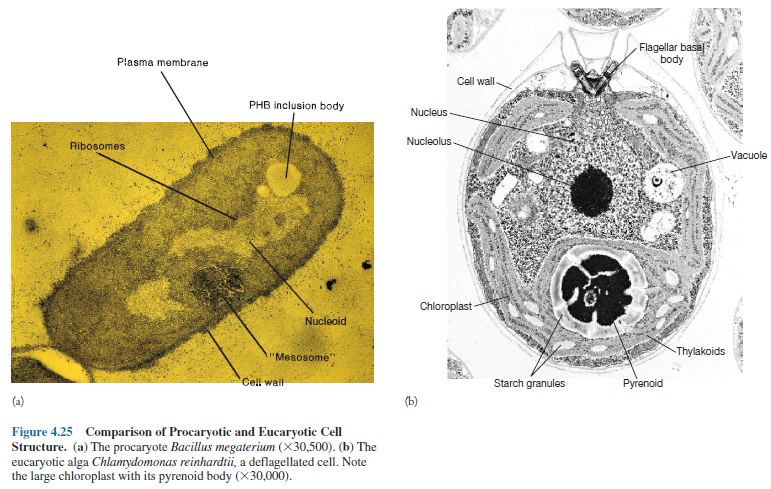

Although

chloroplasts are quite variable in size and shape, they share many structural

features. Most often they are oval with dimensions of 2 to 4 µm by 5 to 10 µm,

but some algae possess one huge chloroplast that fills much of the cell. Like

mitochondria,

chloroplasts

are encompassed by two membranes (figure 4.16). A matrix, the stroma, lies

within the inner membrane. It contains DNA, ribosomes, lipid droplets, starch

granules, and a complex internal membrane system whose most prominent

components are flattened, membrane-delimited sacs, the thylakoids. Clusters of two

or more thylakoids are dispersed within the stroma of most algal chloroplasts

(figures 4.16 and 4.25b). In some groups of algae, several disk-like

thylakoids are stacked on each other like coins to form grana (s., granum).

Photosynthetic

reactions are separated structurally in the chloroplast just as electron

transport and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are in the mitochondrion. The

formation of carbohydrate from CO2 and water, the dark reaction, takes place in

the stroma.

The

trapping of light energy to generate ATP, NADPH, and O2, the light reaction,

is located in the thylakoid membranes, where chlorophyll and electron transport

components are also found.

The

chloroplasts of many algae contain a pyrenoid (figure 4.25b), a dense

region of protein surrounded by starch or another polysaccharide. Pyrenoids

participate in polysaccharide synthesis.

The Nucleus

and Cell Division

The

cell nucleus is by far the most visually prominent organelle. It was discovered

early in the study of cell structure and was shown by Robert Brown in 1831 to

be a constant feature of eukaryotic cells. The nucleus is the repository for

the cell’s genetic information and is its control center.

Nuclear

Structure

Nuclei

are membrane-delimited spherical bodies about 5 to 7 µm in diameter (figures

4.2 and 4.25b). Dense fibrous material called chromatin can be seen

within the nucleoplasm of the nucleus of a stained cell. This is the

DNA-containing part of the nucleus. In nondividing

cells, chromatin exists in a dispersed condition, but condenses during mitosis

to become visible as chromosomes.

Some

nuclear chromatin, the euchromatin, is loosely organized and contains those

genes that are expressing themselves actively.

Heterochromatin

is coiled more tightly, appears darker in the electron microscope, and is not

genetically active most of the time. Organization of DNA in eucaryotic nuclei The

nucleus is bounded by the nuclear envelope (figures 4.2 and 4.25b), a

complex structure consisting of inner and outer membranes separated by a 15 to

75 nm perinuclear space. The envelope is continuous with the ER at several

points and its outer membrane is covered with ribosomes. A network of intermediate

filaments, called the nuclear lamina, lies against the inner surface of the

envelope and supports it. Chromatin usually is associated with the inner

membrane.

Many

nuclear pores penetrate the envelope (figure 4.17), each pore formed by a

fusion of the outer and inner membranes.

Pores

are about 70 nm in diameter and collectively occupy about 10 to 25% of the

nuclear surface. A complex ring-like arrangement of granular and fibrous

material called the annulus is located at the edge of each pore.

The

nuclear pores serve as a transport route between the nucleus and surrounding

cytoplasm. Particles have been observed moving into the nucleus through the

pores. Although the function of the annulus is not understood, it may either

regulate or aid the movement of material through the pores. Substances also

move directly through the nuclear envelope by unknown mechanisms.

The Nucleolus

Often

the most noticeable structure within the nucleus is the nucleolus (figures 4.2

and 4.25b). A nucleus may contain from one to many nucleoli. Although

the nucleolus is not membrane-enclosed, it is a complex organelle with separate

granular and fibrillar regions.

It is

present in nondividing cells, but frequently disappears during mitosis. After

mitosis the nucleolus reforms around the nucleolar organizer, a particular part

of a specific chromosome.

The

nucleolus plays a major role in ribosome synthesis. The nucleolar organizer DNA

directs the production of ribosomal RNA (rRNA). This RNA is synthesized in a

single long piece that then is cut to form the final rRNA molecules. The

processed rRNAs next combine with ribosomal proteins (which have been synthesized

in the cytoplasmic matrix) to form partially completed ribosomal subunits. The

granules seen in the nucleolus are probably these subunits. Immature ribosomal

subunits then leave the nucleus, presumably by way of the nuclear envelope

pores and mature in the cytoplasm.

Mitosis and

Meiosis

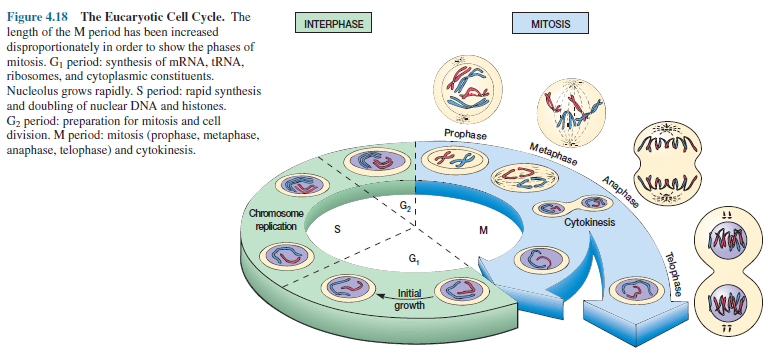

When a eucaryotic microorganism reproduces, its genetic material must be duplicated and then separated so that each new nucleus possesses a complete set of chromosomes. This process of nuclear division and chromosome distribution in eucaryotic cells is called mitosis. Mitosis actually occupies only a small portion of a microorganism’s life as can be seen by examining the cell cycle (figure 4.18).

The cell cycle is the total sequence of events in the growth-division

cycle between the end of one division and the end of the next. Cell growth

takes place in the interphase, that portion of the cycle between periods of

mitosis. Interphase is composed of three parts. The G1 period (gap 1 period) is

a time of active synthesis of RNA, ribosomes, and other cytoplasmic constituents

accompanied by considerable cell growth.

This

is followed by the S period (synthesis period) in which DNA is replicated and

doubles in quantity. Finally, there is a second gap, the G2 period, when the

cell prepares for mitosis, the M period, by activities such as the synthesis of

special division proteins. The total length of the cycle differs considerably

between microorganisms, usually due to variations in the length of G1.

Mitotic

events are summarized in figure 4.18. During mitosis, the genetic material

duplicated during the S period is distributed equally to the two new nuclei so

that each has a full set of genes.

There are four phases in mitosis. In prophase, the chromosomes— each with two chromatids—become visible and move toward the equator of the cell. The mitotic spindle forms, the nucleolus disappears, and the nuclear envelope begins to dissolve. The chromosomes are arranged in the center of the spindle during metaphase and the nuclear envelope has disappeared.

During anaphase the chromatids

in each chromosome separate and move toward the opposite poles of the spindle.

Finally during telophase the chromatids become less visible, the nucleolus

reappears, and a nuclear envelope reassembles around each set of chromatids to

form two new nuclei.

Mitosis

in eucaryotic microorganisms can differ from that pictured in figure 4.18. For

example, the nuclear envelope does not disappear in many fungi and some

protozoa and algae (figure 4.19).

Frequently

cytokinesis, the division of the parental cell’s cytoplasm to form new cells,

begins during anaphase and finishes by the end of telophase. However, mitosis

can take place without cytokinesis to generate multinucleate or coenocytic

cells.

In

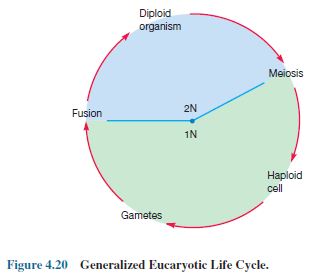

mitosis the original number of chromosomes is the same after division and a

diploid organism will remain diploid or 2N (i.e., it still has two copies of

each chromosome). Frequently a microorganism reduces its chromosome number by

half, from the diploid state to the haploid or 1N (a single copy of each

chromosome).

Haploid

cells may immediately act as gametes and fuse to reform diploid organisms or

may form gametes only after a considerable delay (figure 4.20). The process by

which the number of chromosomes is reduced in half with each daughter cell

receiving one complete set of chromosomes is called meiosis. Life cycles can be

quite complex in eucaryotic microorganisms; a classic example is the life cycle

of Plasmodium, the cause of malaria.

Meiosis

is quite complex and involves two stages. The first stage differs markedly from

mitosis. During prophase, homologous chromosomes come together and lie

side-by-side, a process known as synapsis. Then the double-stranded chromosomes

from each homologous pair move to opposite poles in anaphase. In contrast, during

mitotic anaphase the two strands of each chromosome separate and move to opposite

poles. Consequently the number of chromosomes is halved in meiosis but not in

mitosis. The second stage of meiosis is similar to mitosis in terms of

mechanics, and single-stranded chromosomes are separated. After completion of meiosis

I and meiosis II, the original diploid cell has been transformed into four

haploid cells.

External Cell

Coverings

Eucaryotic

microorganisms differ greatly from procaryotes in the supporting or protective

structures they have external to the plasma membrane. In contrast with most bacteria,

many eucaryotes lack an external cell wall. The amoeba is an excellent example.

Eucaryotic cell membranes, unlike most procaryotic membranes, contain sterols

such as cholesterol in their lipid bilayers, and this may make them mechanically

stronger, thus reducing the need for external support. (However, as mentioned

on page 47, many prokaryotic membranes are strengthened by hopanoids.)

Of

course many eucaryotes do have a rigid external cell wall. Algal cell walls

usually have a layered appearance and contain large quantities of

polysaccharides such as cellulose and pectin. In addition, inorganic substances

like silica (in diatoms) or calcium carbonate (some red algae) may be present.

Fungal cell walls normally are rigid.

Their

exact composition varies with the organism; but usually, cellulose, chitin, or

glucan (a glucose polymer different from cellulose) are present. Despite their

nature the rigid materials in eucaryotic walls are chemically simpler than

procaryotic peptidoglycan.

Many protozoa and some algae have a different external structure, the pellicle (figure 4.16a). This is a relatively rigid layer of components just beneath the plasma membrane (sometimes the plasma membrane is also considered part of the pellicle). The pellicle may be fairly simple in structure.

For example, Euglena has a

series of overlapping strips with a ridge at the edge of each strip fitting

into a groove on the adjacent one. In contrast, ciliate protozoan pellicles are

exceptionally complex with two membranes and a variety of associated

structures. Although pellicles are not as strong and rigid as cell walls, they

do give their possessors a characteristic shape.

Cilia and

Flagella

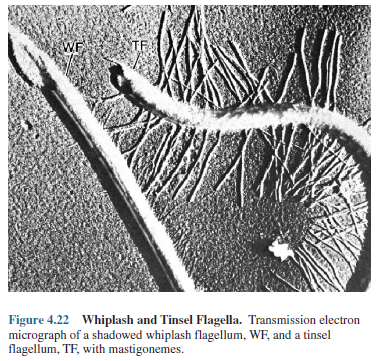

Cilia (s., cilium) and flagella (s., flagellum) are the most prominent organelles associated with motility. Although both are whip-like and beat to move the microorganism along, they differ from one another in two ways. First, cilia are typically only 5 to20 µm in length, whereas flagella are 100 to 200 µm long. Second, their patterns of movement are usually distinctive (figure 4.21).

Flagella

move in an undulating fashion and generate planar or helical waves originating

at either the base or the tip. If the wave moves from base to tip, the cell is

pushed along; a beat traveling from the tip toward the base pulls the cell through

the water. Sometimes the flagellum will have lateral hairs called flimmer

filaments (thicker, stiffer hairs are called mastigonemes).

These

filaments change flagellar action so that a wave moving down the filament

toward the tip pulls the cell along instead of pushing it. Such a flagellum often

is called a tinsel flagellum, whereas the naked flagellum is referred to as a

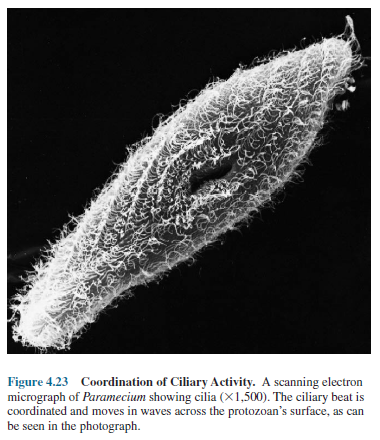

whiplash flagellum (figure 4.22). Cilia, on the other hand, normally have a

beat with two distinctive phases. In the effective stroke, the cilium strokes

through the surrounding fluid like an oar, thereby propelling the organism

along in the water.

The

cilium next bends along its length while it is pulled forward during the

recovery stroke in preparation for another effective stroke. A ciliated

microorganism actually coordinates the beats so that some of its cilia are in

the recovery phase while others are carrying out their effective stroke (figure

4.23). This coordination allows the organism to move smoothly through the

water.

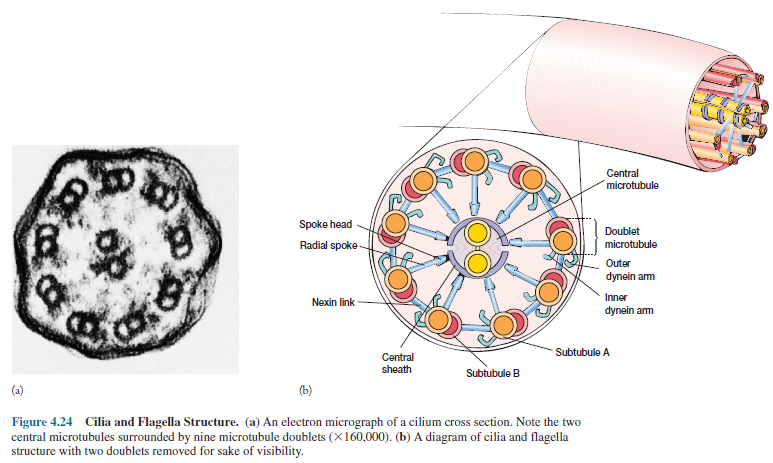

Despite their differences, cilia and flagella are very similar in ultrastructure. They are membrane-bound cylinders about 0.2 µm in diameter. Located in the matrix of the organelle is a complex, the axoneme, consisting of nine pairs of microtubule doublets arranged in a circle around two central tubules (figure 4.24). This is called the 9 + 2 pattern of microtubules.

Each doublet also has pairs

of arms projecting from subtubule A (the complete microtubule) toward a

neighboring doublet. A radial spoke extends from subtubule A toward the

internal pair of microtubules with their central sheath. These microtubules are

similar to those found in the cytoplasm. Each is constructed of two types of

tubulin subunits, α- and β-tubulins, that resemble the contractile protein

actin in their composition.

A basal

body lies in the cytoplasm at the base of each cilium or flagellum. It is a

short cylinder with nine microtubule triplets around its periphery (a 9 + 0

pattern) and is separated from the rest of the organelle by a basal plate. The

basal body directs the construction of these organelles. Cilia and flagella

appear to grow through the addition of preformed microtubule subunits at their

tips.

Cilia

and flagella bend because adjacent microtubule doublets slide along one another

while maintaining their individual lengths.

The

doublet arms (figure 4.24), about 15 nm long, are made of the protein dynein. ATP

powers the movement of cilia and flagella, and isolated dynein hydrolyzes ATP.

It appears that dynein arms interact with the B subtubules of adjacent doublets

to cause the sliding.

The

radial spokes also participate in this sliding motion. Cilia and flagella beat

at a rate of about 10 to 40 strokes or waves per second and propel

microorganisms rapidly. The record holder is the flagellate Monas

stigmatica, which swims at a rate of 260 µm/second (approximately 40 cell

lengths per second); the common euglenoid flagellate, Euglena gracilis, travels

at around 170 µm or 3 cell lengths per second. The ciliate protozoan Paramecium

caudatum swims at about 2,700 µm/second (12 lengths per second). Such

speeds are equivalent to or much faster than those seen in higher animals.

Comparison of

Procaryotic and Eucaryotic Cells

A

comparison of the cells in figure 4.25 demonstrates that there are many fundamental

differences between eucaryotic and procaryotic cells. Eucaryotic cells have a

membrane-enclosed nucleus. In contrast, procaryotic cells lack a true, membrane-delimited

nucleus. Bacteria and Archaea are procaryotes; all other organisms—algae, fungi,

protozoa, higher plants, and animals—are eucaryotic. Procaryotes normally are

smaller than eucaryotic cells, often about the size of eucaryotic mitochondria

and chloroplasts.

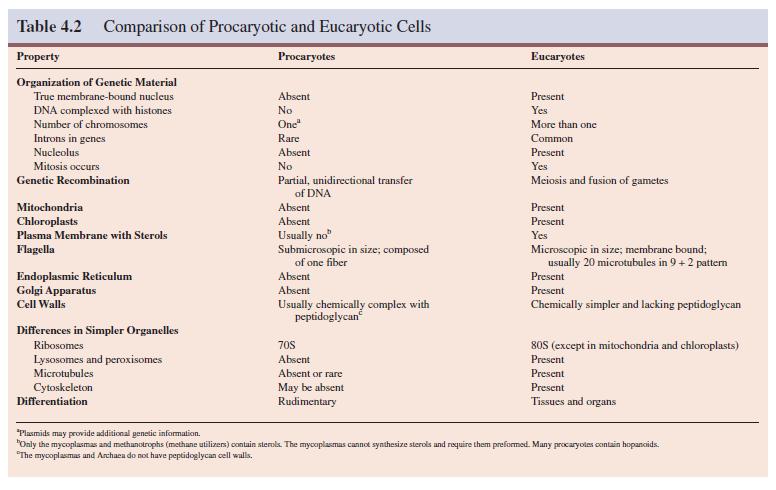

The presence of the eucaryotic nucleus is the most obvious difference between these two cell types, but several other major distinctions should be noted. It is clear from table 4.2 that procaryotic cells are much simpler structurally. In particular, an extensive and diverse collection of membrane-delimited organelles is missing.

Furthermore, procaryotes are simpler functionally in several

ways. They lack mitosis and meiosis, and have a simpler genetic organization.

Many complex eucaryotic processes are absent in procaryotes: phagocytosis and

pinocytosis, intracellular digestion, directed cytoplasmic streaming, ameboid

movement, and others.

Despite the many significant differences between these two basic cell forms, they are remarkably similar on the biochemical level as will be discussed in succeeding chapters. Procaryotes and eucaryotes are composed of similar chemical constituents. With a few exceptions the genetic code is the same in both, as is the way in which the genetic information in DNA is expressed.

The principles underlying metabolic processes and most of the more important metabolic pathways are identical. Thus beneath the profound structural and functional differences between procaryotes and eucaryotes, there is an even more fundamental unity: a molecular unity that is basic to all known life processes.

No comments:

Post a Comment